Governor signs criminal reform bills

Published 11:19 am Monday, April 3, 2017

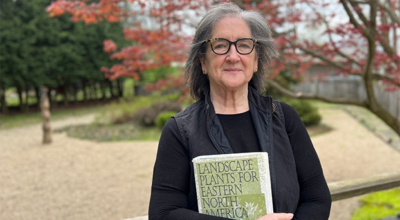

- Gov. Rick Snyder (center) poses for a photo with Sen. John Proos and other officials during the signing of a comprehensive criminal justice bill package Thursday in Kalamazoo. The legislation was spearheaded by Proos, and calls for numerous reforms aimed at reducing recidivism rates. (Submitted photo)

When it comes ending the cycle of crime and incarceration that many of Michigan’s offenders find themselves in, Sen. John Proos is looking to make the state’s criminal justice system work smarter, not harder.

Last week, the Republican lawmaker and many of his colleagues in Lansing came one step closer to finally slamming the revolving door of Michigan’s prisons shut.

Gov. Rick Snyder signed a package of bills aimed at reforming the state’s criminal justice system into law Thursday, during a ceremony in Kalamazoo. The legislation, spearheaded by Proos, makes numerous changes to the way the state handles its correctional facilities and court system and is designed to reduce recidivism rates.

The package, which contains 18 bills sponsored by Proos and nearly a dozen other state senators, calls for a number of overhauls , including:

• Creating a Parole Sanction Certainty program in participating Michigan counties, aimed at reducing recidivism among high risk prison parolees.

• Limiting the amount of jail time offenders are required to serve for committing technical violations (not new crimes) while on probation.

• Allowing judges the ability to end an offender’s probation sentence early for good behavior.

• Improving the state’s Swift and Sure probation program, including expanding the number of offenders who are eligible to particpate.

Proos — who represents voters in Berrien, Cass and St. Joseph counties — led the effort earlier this year to get the package of bills moved through Michigan’s Senate and House. The senator sponsored similar legislation last year, though it failed to make it past the House, he said.

According to Proos, the package is meant to focus the state’s time, energy — and tax dollars — on effective programs that have greater success of rehabilitating criminals, rather than continually spending resources on programs that do not.

At the moment, the state spends $2 billion on the Michigan Department of Corrections. The average annual cost of housing a prisoner in jail is $34,000, Proos said.

“All that [spending] takes away from opportunities for us to invest in areas such as education, road funding or revenue sharing,” Proos said. “Every general fund dollar we spend on the department of corrections is one that can’t be spent in a more productive manner.”

The state currently has 100,000 people under state supervision, 42,000 of whom are incarcerated in prison. Of those prisoners, 90 percent are expected to reenter to society, the state senator said.

Unfortunately, many of those who are currently serving time will reoffend once they are released. Around half of new state prisoners are admitted because they violated the terms of their probation or parole, Proos said.

To combat the problem, Proos and other state lawmakers sought to implement best correctional practices from other states to bring down recidivism rates, which should not only save taxpayer dollars in the long run but also bring down crime rates.

“A safe community is a productive community,” he said.

Among the initiatives Proos pushed for is the expansion of Michigan’s Swift and Sure sanction probation program, which the senator helped create in 2012.

The program — which is in place at, among other Michigan jurisdictions, Berrien and Cass counties — is designed to give high-risk criminals intensive supervision, with strict consequences for violations, Proos said.

“It is a last chance effort to divert criminals from a life of crime that would otherwise sent them to prison,” he said.

Under the new legislation, more offenders will be able to join the program, Proos said.

The new Parole Sanction Certainty program created by the bills is modeled after Swift and Sure, only designed for high-risk parolees, Proos said.

The legislation also incorporates tried-and-true practices from other parts of the country.

For example, the department of corrections will focus more efforts at rehabilitating younger offenders, 18 to 22 years old, including separating them from older prisoners in an effort to keep them from learning tricks and tactics from more seasoned criminals. Similar initiatives in other states have been effective, Proos said.

In spite of the successful enactment of the reforms, Proos said he is already looking into additional improvements to the state’s criminal justice system, including increased data sharing between the department of corrections and other state agencies.

“There are a lot of ideas out there, and I look forward to pursuing them in the years ahead,” he said.