Divers preserve Lake Michigan wonders

Published 2:14 pm Thursday, March 21, 2013

CASSOPOLIS — Divers like Jim Scholz prize “deadeyes” and portholes.

Deadeyes and blocks were used in the rigging of old-time sailing ships to gain mechanical advantage through use of compound pulleys.

Before powered winches, manpower was the only working force on board.

“Generally, the wood is very hard; white oak in the Great Lakes,” he said. “They’re one of the treasures you can find on a wreck that you can identify. We don’t take anything out of the preserve. We photograph, measure and document them, so, hopefully, they’ll be there for years to come for more divers to see.”

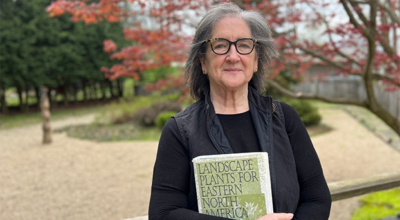

Scholz is president of the Southwest Michigan Underwater Preserve. There are 13 preserves surrounding Michigan. His preserve extends from the state line north to Holland and five miles from shore or 130 feet deep, whichever is less.

His program “What Lies Beneath” doubles as outreach because “we’re looking for more wrecks, more leads, more history to discover,” Scholz said.

Fishermen help locate wrecks.

“If you find something and pass it on to us, we’ll name it whatever you want,” he said.

Eight thousand ships wrecked in the Great Lakes — 3,000 in Lake Michigan, which is 307 miles long and up to 118 miles wide, and 300 in its lower quadrant.

Lake Michigan is the only Great Lake entirely within the United States.

Scholz, of Sister Lakes, highlighted a number of shipwrecks Tuesday night for Cass County Historical Society at Cass District Library.

“The Farmer is one I am personally studying,” he said. “It could be the oldest shipwreck in Lake Michigan. It was built in 1827 in Salem, Ohio. It sailed in Lake Erie and was registered in Cleveland, Milwaukee and Chicago, sailing to St. Joseph and Michigan City. It was lost on its first voyage in 1863 in a squall. The lumber it was carrying washed up near New Buffalo. There’s a discrepancy of whether there were five or seven on board, but all were lost. The ship itself was never found,” although “Mac’s Wreck” off the Cook plant might fit the bill.

“I’m not convinced. I want to be certain,” Scholz said.

The Ironsides, a wooden steamer, sank on Sept. 20, 1864.

The Havana, lost in 1887, “is a wreck we dive quite often up in St. Joe. It’s a two-masted schooner, as was the Farmer.”

The Rockaway went down Nov. 19, 1891, off South Haven. “It was the subject of extensive underwater archaeology a few years ago. They laid out grids, moved a lot of sand and recovered artifacts, now sitting in a basement somewhere up in Lansing because anything on the bottom of the lake belongs to the State of Michigan.”

The Hennepin sank Aug. 8, 1927. “It was the first self-unloader on Lake Michigan,” he said, “converted from a barge where they had to hand-unload grain or coal. They developed this conveyor belt, which is basically the same design used today. This wreck was identified by people looking for Northwest Airlines Flight 2501,” including author Clive Cussler.

Ann Arbor No. 5 was a car ferry submerged in 1970 off South Haven.

North Shore Tug “went down in the 1980s under mysterious circumstances,” Scholz said. “It’s 150 feet deep in the Saugatuck area. This vessel is not very large and hard to locate. Winter storms push it around.”

The Joseph P. Farnum was an 1887 wooden steamer leaving St. Joseph bound for Escanaba. “They had a fire in the boiler room,” he said, “setting the wooden ship on fire. They were adrift. The crew and the captain’s wife were floating around on wreckage” when rescued from South Haven.

Scholz is also a fan of tall ships, such as Friends Good Will, operated by South Haven Maritime Museum.

“It will be away a lot this year,” he said, “because the American Tall Ship Association is having a Great Lakes tour. Around Labor Day, Friends Good Will will be part of a recreation of the Battle of Lake Erie in the War of 1812.”

Fingertip-sized zebra mussels, each filtering a quart of water daily, improve clarity by removing silt, algae and micro-organisms.

“We had a wreck 80 feet long by the Cook plant, and we could see from the bow to the stern,” Scholz said. “These ‘green’ photos are taken with natural light in 72 feet of water. No artificial lights. Visibility’s fantastic. The lake used to be green-blue. Now, it’s crystal blue.”

Legendary storms

Nov. 10, 1835 — In 1812, Chicago was Fort Dearborn, population 40 — less than St. Joseph. By the 1830s, roads existed only as two-track paths. No railroads, either. Boats offered the most convenient travel.

Nov. 9-11, 1913 — The Blizzard of 1978 “was a drop in the bucket by comparison.”

Nov. 11, 1940 — Armistice Day Blizzard. Fifty-nine sailors lost.

“It’s almost as much fun looking for a pot of gold as finding one.”

— Jim Scholz of Sister Lakes, president of the Southwest Michigan Underwater Preserve in Lake Michigan