Story of century-old Fort St. Joseph rock

Published 3:43 pm Wednesday, November 14, 2012

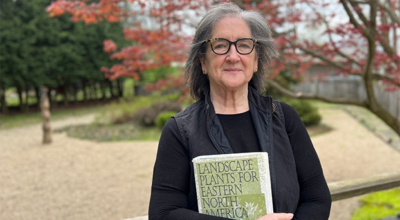

The big rock on Bond Street acknowledges Fort St. Joseph’s 1691-1761 existence. The stone was dedicated July 4, 1913, it says at the top of the stairs. The Michigan historic site plaque states the French fort built here in 1691 controlled southern Michigan’s principal Indian trade routes. Missionaries and fur traders were here already. The fort became a British outpost in 1761. Two years later it was one of the forts seized by Indians during the uprising of Chief Pontiac. Still later, traders made it their headquarters. In 1781 Spanish raiders ran up the flag of Spain at the fort for a few hours. Leader photo/JOHN EBY

Did you ever look at the seven-ton boulder commemorating Fort St. Joseph and wonder how it got there?

Especially 100 years ago?

The fort marker at the south city limits happened in 1912.

Those who helped pay to move the rock had their names listed on a piece of paper placed in a time capsule buried beneath it.

A 1966 Daily Star article reported the sealed copper box also contained copies of it and the Daily Sun, coins, an historical primer on the fort, names of Niles lawyers, dentists, doctors, churches, ministers, as well as all postmasters since 1828, a history of the Fort St. Joseph Historical Society, fraternal societies of Niles, monument photos, industrial and commercial concerns and a list of federal, state, Berrien County and city officials of the time.

The dedication of the Fort St. Joseph site and unveiling of the huge rock drew national attention.

In 1966, Gertrude Johnson, director of the Fort St. Joseph Museum, told the history of the big rock.

In 1910, leading citizens decided something should be done to mark the spot.

A search began for a “suitable” rock.

One day, Mr. Beeson came across a stone four feet in diameter in swampland on Peter Malone’s farm on West River Road.

Niles men contracted with a South Bend firm to move the boulder.

Past experience made the Indiana movers wary of such jobs unless they were paid by the hour.

Two years later when the rock was dug out, its size was the talk of the area.

The South Bend firm estimated the cost at $400, but, by the time the rock arrived at the fort site, the bill was $1,000. The $400 ran out when it reached the road.

Each interested man went to the bank and signed his name to a $1,000 note so movers could complete the job.

“There won’t be much left of Brandywine Creek bridge after we take the rock across it,” said Ralph Ballard of the move.

A great amount of lumber was borrowed from dealer Carmi Smith, and men built a bridge over the existing bridge.

After the stone, cradled in a huge gondola-type cart, crossed the creek, lumber that was still usable was returned to Smith.

Hillis Smith, who donated the two-headed lamb to the museum, was also an mason and built the platform.

The day of the dedication there was a two-mile parade through town with everyone who owned an automobile driving in the parade.

Chicago newspapers described the floats as outstanding.

A former Niles man, Judge O.W. Coolidge, delivered the dedication address.

The monument was draped with a large American flag stitched by Mrs. George Gillam.

The honor of unveiling the boulder went to Mrs. John Ferguson, president of Fort St. Joseph Historical Society.

Also taking part was Ballard, vice president of the society, and Miss Sarah Machin, society treasurer.

Scores of other Niles women lent a helping hand raising money for the historical marker. School children and teachers contributed nickels.

Judge Coolidge told the large gathering, had these people failed, the fort of the four banners, so rich in romantic history, might have passed entirely from the memory of man.

After the ceremony, everyone trooped down the road to Beeson’s grove, where lemonade and ice cream were sold to raise the last of the money.