Michiana manufacturing businesses cite growing workforce as key to growth

Published 7:36 pm Sunday, March 1, 2020

- Brooke Kostielney, the director of marketing and company culture, and Dominick Saratore, president of C&S Machine, stand in the middle of the factory.

Think of the word “manufacturing.” What are its associations?

Dirty floors, oily equipment, dingy warehouses, poor conditions and poor pay. That, said Brooke Kostielney, is what people typically associate with manufacturing.

The director of marketing and company culture of C&S Machine said so in a spacious climate-controlled parts plant with ample sunlight, clean floors and a souped-up break room.

Cars, companies in critical condition, job layoffs and blighted buildings. That, said Jeff Rea, is what people typically associate with the Michigan manufacturing industry.

The Greater Niles Chamber of Commerce president and CEO said so from his office overlooking businesses that have helped make a Michiana economy strong.

To Rea, Michiana manufacturing is a community of successful small, mid-size, even large companies that are growing in local and global markets, so long as workforce needs are met.

To Kostielney, Michiana manufacturing is at its best at C&S, 2929 Saratore Dr., Niles.

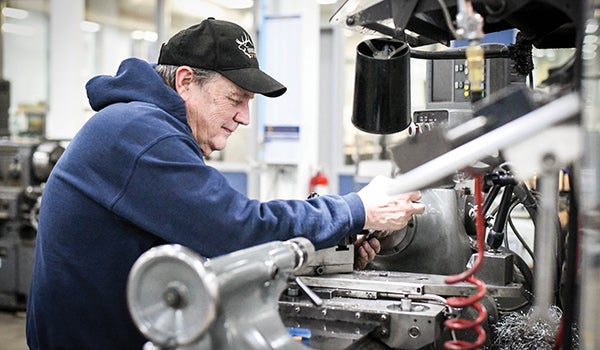

On a drab November morning, the stark gray plant building is contrasted by a rising sun that radiates inside the climate-controlled plant, lighting up the clean floors, well-maintained machines and employees that carefully go about their skilled work.

The company has come a long way since its inception in 1966, said President Dominick Saratore. His father, Joseph, opened shop in Buchanan as a tools supplier for area businesses Bendix Corporation and the Studebaker Corporation.

Joseph later expanded his company, adding on two additional buildings and finding a successful niche in the aerospace industry, creating ultra-precision parts with ultra-delicate tools for Fortune 1,000 companies.

Joseph can now often be found on the floor, working alongside employees.

Since taking over in 2010, Saratore has implemented lean manufacturing practices, cutting down on waste without cutting productivity in the process. The practice led to the creation of a new plant in Bertrand Township in an industrial park about two years ago.

Now, C&S is only growing, Saratore said, sporting an ugly Christmas sweater for a staff-wide contest later that day.

“We’re in a very nice spot for our location, for our business,” Saratore said. “We continually say we’re in the sweet spot of the country.”

Saratore cited proximity to major metropolitan areas, a large manufacturing business base, inexpensive cost of living and a well-trained workforce as reasons why Michiana is great for industry.

Rea, in a separate interview, agreed with Saratore’s statement. As the leader of not only the Niles area’s chamber but neighboring South Bend’s, he said economic development has been successful in the area.

He likened good economic development happening in Michiana to a quote from the baseball movie, “Moneyball.”

“You can actually win a lot of games hitting, getting on base, walks, singles and doubles,” he said. “You don’t need to hit a homerun.”

The home run Rea alludes to is an old-school mentality on economic development: placing most of one’s resources in hopes of a big company coming into town.

Only about 200 of such investments happen nationally each year, Rea said. Usually, they occur in the southeast or southwest, not what has been historically known as flyover country.

While one investment was made — the estimated $1 billion Indeck Niles Energy Center natural gas plant — Michiana finds year-to-year and day-to-day success in retaining and strengthening the strong business base and entrepreneurial spirit already present.

What the manufacturing community needs now is to look past its profits and growth, Rea said.

“When people think of economic development, they think of business attraction and development and expansion,” Rea said. “Yeah, but you got to have good community planning. You have to have a nice zoning ordinance. You have to have a good K-12 system, and you have to have good training opportunities.”

In essence, for businesses to stay strong and become stronger, they must work to not only provide good wages, benefits and perks to employees, they must help create a larger community that supports the workforce and trains its future members properly.

“We’re quoting. We’re winning. We’re adding $1 million equipment, so the future looks strong,” said Peter Carpenter.

Carpenter is the plant manager of Pilkington NSG, 2121 W. Chicago Road, Niles, across US-12 from C&S Machine. He spoke from his desk, occasionally breaking away to say farewells to fellow employees who were en route to a holiday break.

During his 22 years at NSG, eight as a manager, Carpenter said he has come to pride himself on providing safe jobs and great opportunities for pay, benefits and upward mobility.

At the end of 2019, the vehicle window manufacturer employed upwards of 350 people. Carpenter said he is looking for more. Outside his office window is a sign encouraging passersby to apply for jobs.

Finding the right candidate can be difficult in the manufacturing industry, NSG included, he said.

Kostielney, like Carpenter, said that soft skills are important, such as leadership, respect, kindness and timeliness.

So, too, are hard skills. Area school districts offer skilled trades classes, from the culinary arts to vehicle repair, and work to promote jobs in the manufacturing sector as a viable career pathway, such as through weeklong summer camps and job fairs.

Both C&S and NSG develop hard skills by training their employees on-site.

At C&S, using delicate equipment to make even more delicate parts requires lots of hard skill, so the company has continued its long-time, multi-year apprenticeship program, prepping the workers of tomorrow today for well-paying jobs.

But Kostielney said C&S knows that maintaining good workers requires more than wages and benefits.

“There’s a lot of investments made in this facility good for a working environment,” she said.

The natural lighting, a clean workspace and maintained machines are all meant to show how valued employers are.

So, too, are additional amenities. At both ends of the main floor are bathrooms for quick access. At one end of the floor is the break room.

Inside is a chic space with natural light, modern furniture and an assortment of seating spaces. In one corner are rows of vending machines, providing not only sodas and snacks, but healthy wraps and sandwiches.

Rea said efforts to support a strong workforce are needed outside of company doors, too. There is still a stigma of manufacturing jobs being unviable to support an individual or a family, so many parents and school districts have emphasized attending a four-year university over a two-year degree or a skilled trades certification, he said.

The challenge is marketing businesses and jobs to students. As a Niles career-technical education camp proved in July 2019, bringing students to the business, or vice-versa, can be more informative of the types of work available than internet descriptions and estimated wages.

The trend to disavow skilled trades jobs is fading, Rea said, but manufacturing companies must be present in the push to promote skilled trades jobs. Whether it be a career summer camp, a Manufacturing Day event or a regular school day, companies can connect with school districts to show students the jobs that are available in their hometowns.

Erasing past perceptions of what it means to work a manufacturing job are especially pertinent in the context of increasing automation, Rea said. Lean manufacturing principles Saratore spoke of may make it so more products can be made with less people thanks to machines.

The majority of jobs that exist in this potential future may require skilled and semi-skilled labor, rather than the assembly line perceptions of manufacturing past.

Carpenter said meeting potential employees in the middle may be best for business. Rather than just waiting for the workforce to adapt to the jobs available, employers must adapt their job structure to workers, too.

“You have to adapt to the workforce coming in,” he said. “Otherwise, we’ll fail.”